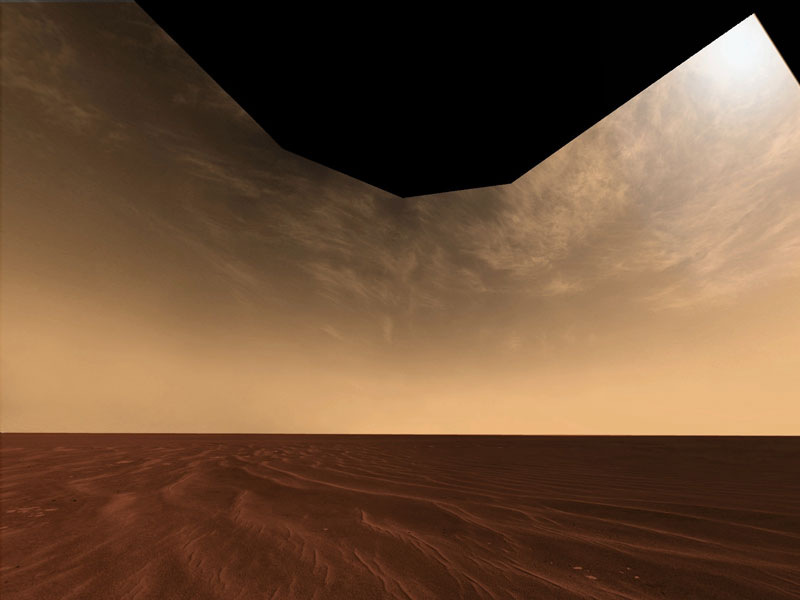

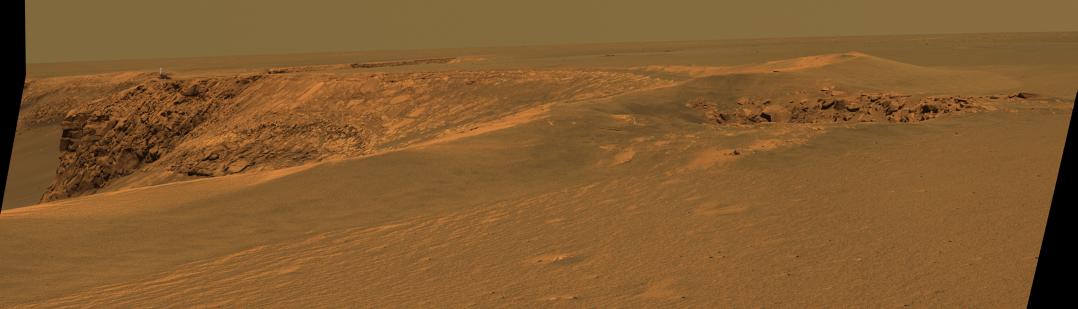

If you could stand on Mars -- what might you see? Like the robotic Opportunity rover rolling across the red planet, you might well see vast plains of red sand, an orange tinted sky, and wispy light clouds. The Opportunity rover captured just such a vista after arriving at Victoria Crater

earlier this month, albeit in a completely different direction from the large crater. Unlike other Martian vistas, few rocks are visible in this exaggerated color image mosaic. The distant red horizon is so flat and featureless that it appears similar to the horizon toward a calm blue ocean on Earth. Clouds on Mars can be composed of either carbon dioxide ice or water ice, and can move quickly, like clouds move on Earth. The red dust in the Martian air can change the sky color above Mars from the blue that occurs above Earth toward the red, with the exact color depending on the density and particle size of the floating dust particles.

earlier this month, albeit in a completely different direction from the large crater. Unlike other Martian vistas, few rocks are visible in this exaggerated color image mosaic. The distant red horizon is so flat and featureless that it appears similar to the horizon toward a calm blue ocean on Earth. Clouds on Mars can be composed of either carbon dioxide ice or water ice, and can move quickly, like clouds move on Earth. The red dust in the Martian air can change the sky color above Mars from the blue that occurs above Earth toward the red, with the exact color depending on the density and particle size of the floating dust particles.From the sublime to the ridiculous. All helment and no starship. Theresa Hitchens and Haninah Levine:

After four years and some 35 drafts, the Bush White House has finally released its long-awaited rewrite of the U.S. National Space Policy. Obviously, the administration was keen to get the word out – they quietly posted a 10-page unclassified summary [.pdf] on the Office of Science and Technology Policy’s website at 5 pm on Oct. 6 – the Friday before the Columbus Day long weekend...

While the Clinton version focuses on civil and commercial space, the Bush NSP gives primacy to national security and military space. Example: of Clinton’s five goals for U.S. space programs, two mention national security; of Bush’s six goals, four are related to national security and defense.

While the Clinton policy aimed to highlight international cooperation and collective security in space, the Bush NSP takes a go–it-alone stance, using strong language that asserts U.S. unilateral rights in space while possibly also being intended to "negate" the rights of other space-faring nations. In ominous tones, the document threatens in one section to "dissuade or deter others from either impeding [U.S.] rights or developing capabilities intended to do so" – raising the specter of preemptive action against other nations’ dual-use space technology.

Indeed, even as the Bush policy emphasizes the importance of space security, it goes out of its way to make clear that this security may not, under any circumstances, come from (shudder) international law: "The United States will oppose the development of new legal regimes or other restrictions that seek to prohibit or limit U.S. access to or use of space. Proposed arms control agreements or restrictions must not impair the rights of the United States to conduce research, development, testing and operations or other activities in space for U.S. national interests" [emphasis added].

While the new NSP doesn't go as far as some space hawks wanted it to in openly endorsing the strategy of fighting "in, from and through" space, neither has it served to put a blanket – even a thin one – on those ambitions. And in taking a decidedly "us against them" tone, it is likely to further cement the view from abroad that the United States has taken on the role of a "Lone Space Cowboy." And as much as people love John Wayne movies overseas, that will not be a good thing.

Indeed. And some people even with in the Company aren't impressed. The editor at Pravda, for one:

The Bush administration has adopted a jingoistic and downright belligerent tone toward space operations. In a new “national space policy” posted without fanfare on an obscure government Web site, and in recent speeches, it has signaled its determination to be pre-eminent in space — as it is in air power and sea power — while opposing any treaties that might curtail any American action there.

This chest-thumping is being portrayed as a modest extension of the Clinton administration’s space policy issued a decade ago. And so far there is no mention of putting American weapons in space. But the more aggressive tone of the Bush policy may undercut international cooperation on civilian space projects — a goal to which the new policy subscribes — or set off an eventual arms race in space.

The new policy reflects the worst tendencies of the Bush administration — a unilateral drive for supremacy and a rejection of treaties. And it comes just as the White House is desperately seeking help to rein in the nuclear programs of North Korea and Iran. That effort depends heavily on cooperation from China and Russia, two countries with their own active space programs.

The administration regards the policy as a necessary update to reflect how important space is becoming for the American economy and defense. But outside experts who have parsed the language are struck by how forceful and nationalistic it sounds.

Whereas the 1996 policy opened with assurances that the United States would pursue greater levels of partnership and cooperation in space, the new policy states: “In this new century, those who effectively utilize space will enjoy added prosperity and security and will hold a substantial advantage over those who do not. Freedom of action in space is as important to the United States as air power and sea power.”

The only solace is that the new policy does not endorse placing weapons in space or fighting in, through or from space, as the Air Force has been urging. But neither does it rule out these activities.

In keeping with the more muscular stance, the administration is also opposing any negotiations on a treaty to prevent an arms race in outer space — arguing that it may impede America’s ability to defend its satellites from ground-based weapons. That seems shortsighted. An international treaty to keep space free of weapons might well provide greater security than a unilateral declaration that we will do whatever we have to do to preserve our own space assets.

Michael Griffin, the NASA administrator, insisted he did not intend to sound jingoistic when he addressed a conference in Spain this month — but he sure came across that way. He wondered aloud what language future settlers of the Moon and Mars would speak. “Will my language be passed down over the generations to future lunar colonies?” he asked. “Or will another, bolder or more persistent culture surpass our efforts and put their own stamp on the predominant lunar society of the far future?”

We fear the old notion that space might provide the perfect arena for international cooperation may be yielding to a new era of competition — one not seen since the cold war race to the moon.

Don't worry, Mikey. That "bolder and more persistent culture"

is probably quite at home with DynCorp tactics.

is probably quite at home with DynCorp tactics.

No comments:

Post a Comment